When I talk or facilitate a workshop with business leaders, making them all really sad isn’t part of the agenda.

But sometimes it’s exactly what they need. At least for a few minutes.

In particular, there’s an aspect of leadership that always requires emotional awareness. And when we attempt to lead change, there’s always an element of loss. When we lead change, people often have to alter their routines, give up responsibilities and work with new people—all factors that are different from what used to be life as usual.

That can make people sad. Confused. Maybe even angry.

To drive that point home, I sometimes guide leaders or students through the following exercise. To be fair, I certainly didn’t make this up—it’s an amalgamation of a few different ideas that I’ve combined over the past several years—and you’ll likely be able to find various versions of it around the Web. But it’s useful, and I’ve included some scenarios to guide your thinking.

If you’re currently a leader—or if you often find yourself in a role that involves helping leaders deal with change—I encourage you to give this a try.

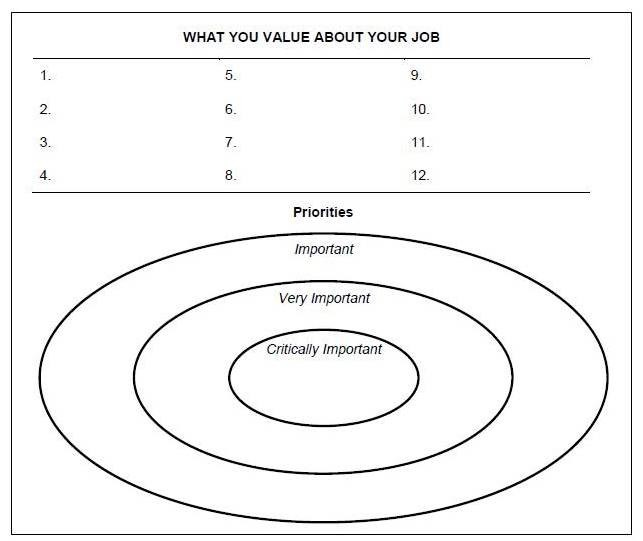

To begin, use the image below to guide how you document your thoughts. You may want to recreate it on a blank piece of paper (or you can download what I’ve used as a handout with groups).

1. Using this format or something like it, list the 12 things that you value the most about your job. This can be the people you work with, the work itself, the physical environment or location—really anything that you value. Be broad in your thinking, but also try to ensure you choose those factors that are most critical to you.

2. Prioritize these 12 “job satisfiers” into three groups, using the concentric ovals on the handout. The “important” group includes factors you value but wouldn’t cause too much difficulty if they were gone. The “very important” group includes those factors that are one step above the “important” ones but aren’t “critical.” The “critical” group includes factors without which the job would become rather dreadful or continually dissatisfying.

3. Now, think about the following scenarios. Try to reflect upon how it might actually feel like to come into work every day under these new conditions given how they may affect what you’ve written down in your groups of “job satisfiers.”

Scenario 1. Due to recent shifts in demand, top management has decided to restructure the organization. Next month, you will report to a new supervisor whom you don’t know. You will also be working directly with a new team of five people whom you have never met. With this restructuring, you will likely have little to no future interaction with your current co-workers or supervisor. There are also rumors that in the near future your specialty area might be combined with those of another department. Layoffs might be on the table.

Scenario 2. The rumors were somewhat true. Your new supervisor explained to you that you would now have additional duties outside of your current area of knowledge and training. Given your new role, you will have more variety in what you do every day but much less say in how your work needs to be accomplished. Furthermore, it seems that these changes—both in your role and across the organization—have made the previous career paths and expected promotion opportunities irrelevant.

Scenario 3. You have gotten settled in somewhat to your new role, but the culture in your new area of the organization feels different. You don’t get your coworkers’ inside jokes and feel like the odd person out most of the time. To further complicate matters, the latest e-mail from your CEO stated that a pay freeze would soon go into effect and that a new benefits plan was being considered. No other details were provided.

4. Reflect upon how you felt as you went through those scenarios. Write down a few thoughts.

What’s powerful about this simple exercise is that it reminds us that whenever a major change happens, many people involved experience the emotions you went through. We all can see very quickly how the changes being proposed or implemented may affect our daily life at work. And that realization typically evokes a strong emotional response.

That’s because major change always involves some kind of loss. It involves leaving something behind.

As such, leading change typically involves the distribution of loss. It involves being aware of what you’re really asking people to do differently and how that might influence their sense of identity, their sense of purpose and comfort at work.

Marty Linsky, a Harvard lecturer and author, describes this well in a TEDx talk he did some years ago. He suggests that much of what we call “leadership” is simply doing what’s expected, and that truly adaptive leadership always involves the distribution of loss.

Here’s that video (the audio is a little rough at the beginning but gets much better after 48 seconds).

When people talk about orchestrating an organizational change, it’s my observation that too little time gets spent on thinking through how people may react. And I think that if we at least anticipated those responses a little better and crafted our processes and our communication around the change a little better in a good-faith spirit of fairness, we’d be met with less resistance.

And maybe, if we did this, we’d be more supportive and influential to those around us.

For more details about how to manage your subscription including e-mails and notifications, click here.